The Spreewald’s (drinking) water shortage

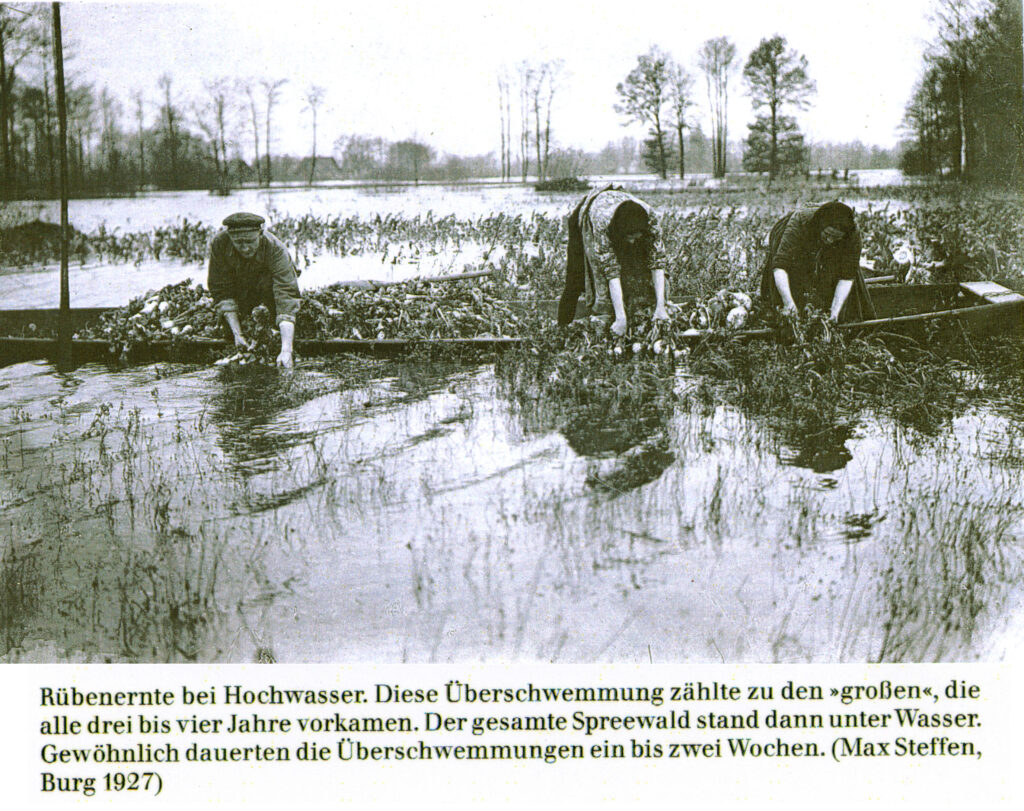

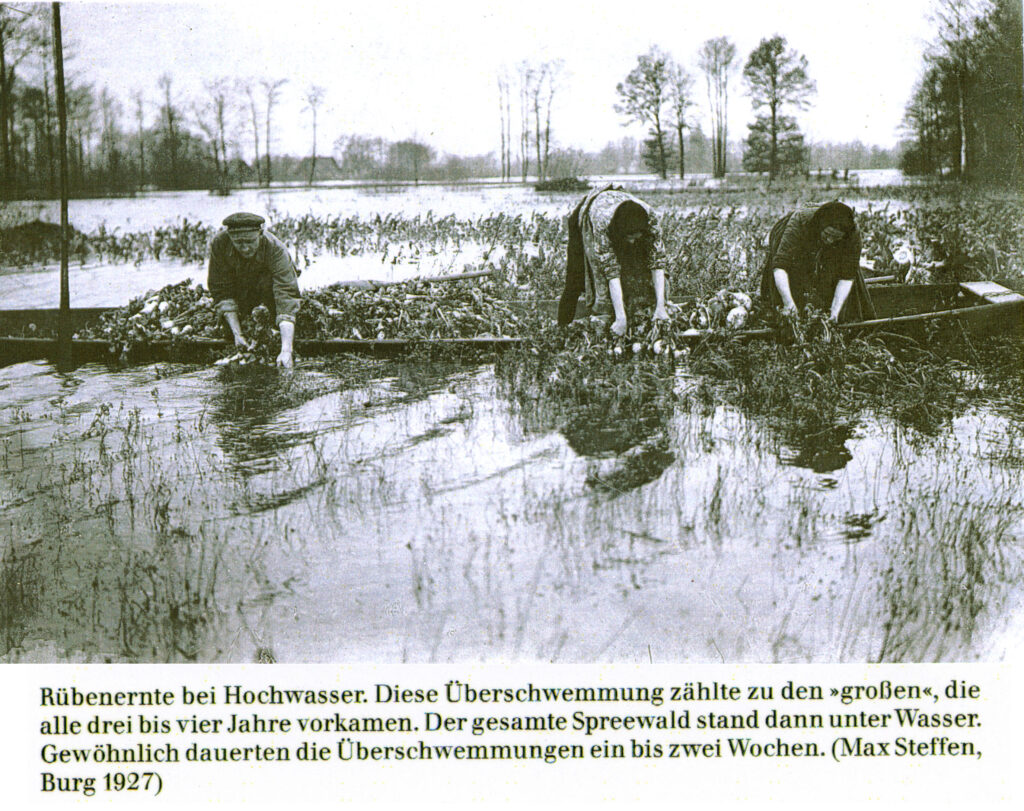

If you live in marshland between numerous water arms, you are unlikely to have a permanent problem with water – at most with too much (floods) or too little (drought). This impression is deceptive and at the same time confirms the common perception of the Spreewald. For centuries, it was also possible to use the water flowing past the house for people and livestock without any problems. With the onset of industrialization and the initially almost non-existent environmental protection laws, the quality of the water deteriorated and its consumption became increasingly questionable.

The Spreewald is almost exclusively influenced by the River Spree – which passes the town of Cottbus on its course just before the Spreewald. A lot of untreated wastewater ended up in the Spree and thus in the Spreewald. A commission examined the water quality at the end of the 1950s and came to the conclusion: “The quality is extremely poor, further extraction is inadmissible!”[1] In addition to extraction for human and animal consumption, the death sentence was also practically pronounced for the animals living in the water. The fauna and flora of the Spreewald were endangered over long stretches of the river, similar to the current problem with ochre pollution from the groundwater contamination caused by open-cast mining. Added to this was the ever-increasing flow of tourists, which resulted in high water consumption in the restaurants – not to mention the fact that the water (toilets!) also had to be disposed of again. The people of the Spreewald not only drew water from the rivers, but also discharged their own wastewater. Almost everyone washed their laundry (usually with curd soap) in the flow. Weeks of severe winter weather with frozen rivers created another problem: ice had to be beaten and thawed, water consumption fell to an absolutely essential level, laundry was left lying around and waste water froze.

Around 1900, tourist traffic increased significantly, with overnight stays in a chamber near the Spreewälder in the early years. A Berlin guest who was watching the cattle watering dates back to this time: “Oh God, the poor animals have to drink the dirty water!” The farmer’s wife kept it to herself that she had prepared the morning coffee for her guest with the same water….

In Leipe, it had become customary to draw water early in the morning and store it for the day, because it was less polluted and not yet churned up by the tourist barges. Some wells were drilled, but the water could only be used boiled at best. With the construction of the drinking water pipeline from Lübbenau in 1962, the last household in Leipe was connected in 1965. The laying of the pipes was accompanied by great difficulties: every trench excavation immediately filled up with water again, so that the pipes had to be laid practically under water. On the six-kilometer route from Lehde to Leipe along the Leiper Weg, 13 streams had to be crossed. With the water supply for the people of Leip now secure, the first inhabitants also began to acquire more comfort: Baths were built, as were water closets (restaurants!) – and with them an even bigger sewage problem than ever before. Initially, collection pits were used, but these have since been converted into 3-chamber biowastewater treatment plants.

Centralized water supply and water disposal has made a significant contribution to improving water quality in recent decades. In addition, there was strict compliance with the discharge regulations along the Upper Spree, the measures taken by the mining cleaners and the more environmentally conscious behavior of the residents. In large parts of the Spreewald, abstraction as service water (garden irrigation) is once again possible, but is subject to approval in order to keep an eye on the overall water management in the Spreewald.

A new feature is the ochre contamination of some watercourses, particularly in the western catchment area of the groundwater. The layers of turf iron ore that occur there are increasingly flowed through by rising groundwater (after the cessation of groundwater lowering caused by opencast mining) and considerably change the water quality. Flora and fauna die off, the water becomes unsightly and visually uninviting. Ochre pollution also occurred in the past after large amounts of precipitation, but this was mostly seasonal and of short duration. This problem is difficult to solve. It will probably take years or decades to return to the original state with the groundwater levels that were common in the past. Until then, liming and resting basins in the catchment area of the surface water, such as in Raddusch and Vetschau, are being used. (see Geotubes)

Another problem is not yet so visible: With the end of coal-fired power generation and thus also with the end of coal mining, a not inconsiderable part of the water supply from the mine drainage system will no longer be available – water shortages could be the result.

“On average in recent years, around 250 to 300 million cubic meters of water from the opencast mines (mainly from the dewatering of LEAG’s mines) have been discharged into the Spree river system every year. In extremely dry summer months, the “sump water” (the water pumped out to keep the open-cast mines dry) can account for up to 50 % to 75 % of the water volume of the Spree at the Leibsch gauge (entrance to the Lower Spreewald). This water is used to keep the water level in the Spreewald stable, support agriculture and ensure the ecological balance in the UNESCO biosphere reserve.

With the end of lignite-fired power generation, these sources are drying up. This poses huge problems for the Spreewald: When the pumps are switched off, the artificial support will no longer be available. At the same time, the remaining open-cast mining pits (such as the Cottbus Baltic Sea) have to be filled, which takes additional water from the Spree. The discharged water often contains high levels of iron (“sooting”), which turns the waters brown and damages the flora and fauna. Purifying this water is extremely costly. Increasing periods of drought in Lusatia exacerbate the deficit, as there is no natural renewal through precipitation.”(Source: Google Gemini)

Peter Becker, 08.02.26

[1] Neues Deutschland, February 27, 1962